Mohamed Sheriff is a Sierra Leonean children’s story writer, playwright, producer and dramatist. He is the author of several beloved children’s books and novellas from Sierra Leone, including Maryama Must Go and Secret Fear. Mohamed Sheriff has been a trainer, coach and publisher of mainly children books. As a children’s books, writer he has a dozen titles to his name, some of them anthologies; as a publisher he has published twice that number of books by other children’s books writers; and as a trainer and coach, he has worked in a number of book development projects that have seen the publication of up to forty books including anthologies for children. He also owns a communications and media company Pampana Communications Publishing and Media Consultancy.

In this interview, he talks to Poda-Poda Stories about his love for children’s literature, why it is important for Sierra Leonean children to see themselves in stories, and the future of publishing for children’s literature.

Poda- Poda: Thank you Mohamed Sherriff, for joining the poda poda. Please tell us about yourself and your work.

Mohamed Sheriff: I write children books, short stories, novellas, and screen, radio and stage plays. I’ve published several books in all of these categories and won a handful of national and international awards for my writings.

Poda-Poda: So how did you get into writing? Have you always been writing or was it something you branched into?

Mohamed Sherriff( MS): I’ve been writing since I was a kid. I did a lot of writing in my ‘head’ back then. I can say I had a hyperactive imagination that would weave a story at the tap of a button in my head. Some incident or chance happening, commonplace or extraordinary, would fire up my imagination into creating a story. I was inspired to tell stories by my mother and my step mum, who were both very good folk storytellers. In the evenings, especially during the long holidays, we - siblings, cousins, other relatives, even neighbours – mainly children, would gather in our backyard or living room and listen to their stories. I was always enthralled by the way my mother told these stories: she would sing, sway, clap her hands, tap her feet and, most captivating to me, mimic the sound of different characters, including animals in her stories, and transport us into their strange, magical or extraordinary world. That was how my love for stories, drama, books and movies evolved. I admired her storytelling so much that I wanted to be a storyteller like her when I grew up. When I was able to read, I discovered books that had similar stories like my mum told, the folk tales, and other kinds of stories, too - realistic fiction for children, and I loved them all.

The more children books I read, the more I loved the idea of writing for children. And then I started reading more complex literature, like novellas, novels, short story collections and plays. My exposure to those kinds of literature inspired me further, strengthening my resolve and nurturing my dream of becoming a writer.

The inspiration for the other important category of my writing, drama, also came from my childhood experiences. When I was little there was a theatre group in our neighbourhood called Guinness Theatre or Drama Group. I think it was sponsored by Guinness, a beverage company. The group conducted rehearsals in a compound on another street just round the corner from our house. Children would flock to the compound to watch the rehearsal and were allowed to stay as long as we behaved ourselves. We got so involved in watching those rehearsals that some of us knew many parts of the plays by heart. I can still remember some of the lines of some of those plays. We had such fun watching them that again I felt I wanted to be involved in theatre when I grew up.

Poda-Poda: How did you make the decision to go into children’s book specifically?

MS: Considering my wonderful childhood experiences at those storytelling sessions, my passion for reading children books ,it was no accident that when eventually I started writing, children books were among the first and has remained an important part of my work as a writer.

My getting into the business of actual writing for children was triggered by my encounter with Macmillan Publishers. Way back in the mid 90s they were very active in Sierra Leone. They organized a workshop to encourage Sierra Leoneans to write for children. With my passion for writing for children, I saw that as a great opportunity, so I attended the workshop, at the end of which, we were encouraged to submit manuscripts. One of the stories I wrote, “Secret Fear” a novella for young readers went on to win an international award and sold thousands of copies.

Much later, I had the opportunity to meet with an organization called CODE (Canadian Organization for the Development of Education). They invited me to a children’s book development workshop in Liberia, where they were engaging local writers and illustrators to develop their own books. After that workshop, they decided to come to Sierra Leone to launch a similar programme for Sierra Leoneans with me as a co-trainer, facilitator and editor. To date, the programme has published 29 books for children.

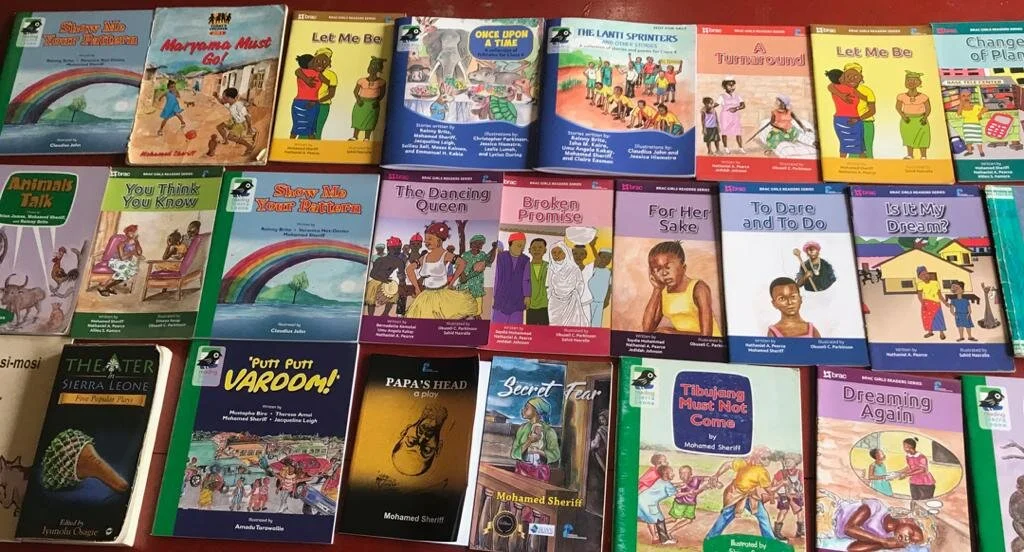

Besides writing for children, I have been a trainer, coach and publisher of mainly children books. As a children’s book writer I have a dozen titles of books to my name, some of them anthologies; as a publisher I have published twice that no of books by other children book writers; and as a trainer and coach, I have worked in a number of book development projects that have seen the publication of up to forty books including anthologies for children.

Poda-Poda: You’ve shared how you’ve published several children’s books. How important is it for Sierra Leonean children to have those books in schools?

MS: It is very important for these books to be in schools, because reading is one of the most effective ways to develop a child’s mind. All other things being equal, a child who engages in reading as a hobby is likely to perform better in school overall than a child who does not. Reading helps children in some very important ways: it broadens their horizons and helps develop their critical thinking and communication skills; and all of this will help them in other subject areas too, not just in literature and English. That is why it is important to encourage children to read. And I would encourage them to start by reading Sierra Leonean books. A lot of foreign children books have been brought to Sierra Leone and distributed to libraries and other institutions. Some of these gather dust on shelves because children don’t read them. This is not to say that it’s not important to read books from other places, but first we must get them interested in reading generally. When children read stories that they can relate to, it excites them and gets them more interested in reading in general. This is what we observed when we distributed books to school reading clubs and libraries through one of our book development and reading projects. The feedback was that children enjoyed reading Sierra Leonean readers than foreign books, because they can identify and engage with the stories and characters. So with all the challenges we are facing with education, one way to help our children from scratch is to promote reading and encourage them to read. It’s one way they can develop their minds against all odds. Reading is one way we can help to improve standards of education in Sierra Leone.

Poda-Poda: How can we support more writers to get into children’s literature?

MS: That is what I have been doing for the past twelve years. My organisation Pampana Communications Publishing, PEN Sierra Leone and our international partners have organized workshops to train writers to write for children. Each of these workshops end in developing manuscripts to be published. But then, because resources are limited, we can only publish what available funds allow us to publish. If the government can support these efforts, it will generate a lot of books.

Everyone one has a part to play in promoting reading. It is the responsibility of our ministry of education to put reading top of their agenda to promote quality education. School authorities should show more interest in promoting reading in their schools. They can include reading in their timetables and have a kind of library hour or reading time to encourage children to read on a regular basis. Parents too have an obligation to encourage their children to read. As parents, we should also be reading to our children and introducing them to stories. Even if it is folk stories, like the ones we used to enjoy listening to as children. That would make children interested in stories either oral or written. The demand for books will encourage more people to write.

Poda-Poda: Let us talk about your other work as a playwright. How did you start that and how has that journey been for you?

MS: When I was writing my dissertation in university, among the option of topics we had was, Recent Trends in Sierra Leonean Theatre. I chose that topic without hesitation. With it I saw an opportunity to watch plays, read play scripts and meet with actors, stage crew and directors during the course of my research. By the time I completed my research and wrote my dissertation, I was absolutely certain I was going to be a playwright. Fast forward to where we are now, I have written well over thirty plays for stage, radio and screen and for the purpose of both entertainment and social change. And I have published, staged and screened a number of these plays and won some national and international awards for playwriting in the process.

It’s been quite an interesting but challenging journey. One of the biggest challenges of particularly theatre in the 80s and 90s was an acute lack of venues for theatrical performances. Up until the mid 80s we had the City Hall as the main venue for theatre. The British council auditorium had always been there, but not accessible to everyone. So the City Hall became a hugely popular venue for plays attracting huge crowds from mid week to the end of the week. Unfortunately in the mid 80’s the then Committee of Management in charge of the Freetown City Council placed a ban on performing plays at the City Hall.

The author, Mohamed Sheriff.

Poda-Poda: Why was there a ban?

MS: All I knew was that the head of the committee said that the hall was not for theatre but other important civic functions. That action seriously affected a lot of groups that relied mainly on that hall for their performances. Many groups simply stopped operating.

A few including my company, Pampana, tried to overcome the challenge by switching focus from producing theatre as art entertainment to producing theatre for social change or development on demand from various organisations that paid for our services. Unlike theatre for art entertainment requiring a built up stage with sometimes elaborate sets in a specified venue, theatre for development can be done anywhere there is space – street corners, market places, village centres, town halls and open community fields

So the ban gave those who were resilient and resourceful an opportunity to create and stage plays for community theatre or theatre for development. But for a number of the groups it was either the end of the road or the beginning of a long period of dormancy.

Poda-Poda: What an interesting journey! It is really unfortunate how theatre declined in Sierra Leone. How can we revive this in Sierra Leone?

MS: That’s a very big question! It’s quite a challenge. There are people working behind the scenes to revive it. However, the biggest challenge is that you cannot do this without money. You have the talents, writers, actors, directors and producers, but to mount your play, you need an audience. To get the audience to go back to theatre, that is a big challenge. The economic situation in the country is such that, most people would have to choose between spending 40,000 -50,000 leones on theatre or using it for something more essential like food or transportation. So that’s our biggest challenge. The government or big businesses could help if they wish to. For a start if they could identify four or five reputable groups, who could perform 2-3 plays per year, and provide them with funds for the productions annually, this would allow those groups to sell tickets at affordable prices and give members of the public the opportunity to watch up to 15 plays per year. That way, drama productions could be sustained over time.

Poda-Poda: When you say “the government”, who specifically are you referring to?

MS: The Ministry of Tourism and Culture. I’ve heard in theatrical circles that the Ministry is interested in reviving theatre, and that the minister has called a number of meetings to discuss the way forward. I hope some progress has been made, and I bet one of the main challenges the ministry would also be facing is lack of funds.

One simple way to work towards reviving theatre is to support groups to produce plays on a regular basis.

Poda-Poda: What advice would you give to writers who want to go into playwriting or children’s literature?

MS: I have met many people who see writing as a way of making money. There is nothing wrong with that. Most dream of publishing best sellers. There’s nothing wrong with that too. Nothing wrong with dreaming big. But you must love to write. You must have the passion for it. Initially the love for writing must be stronger than the desire to make money out of it. That love would let you put your heart and soul into your writing and give you your best seller. Thinking about making money above all else could lead to frustration and disappointment in this field.

To develop excellent writing skills, you must read and keep reading and keep writing. Read, read, read, and write, write, write. And do that with a lot of love. Somewhere along the way, your talent would flourish and be recognized.

Also with so much competition these days, it would be helpful to look at innovative ways you can market your works besides relying on the publisher alone. But first you must develop your skills as a writer.

To buy Mohamed Sheriff’s books, contact him at 82 Sanders Street, Freetown, email him at msaydia@gmail.com or call 076612614.

Interview by Ngozi Cole