“We know we are relevant,” Dunstanette Bodkin on childhood reading and why libraries matter

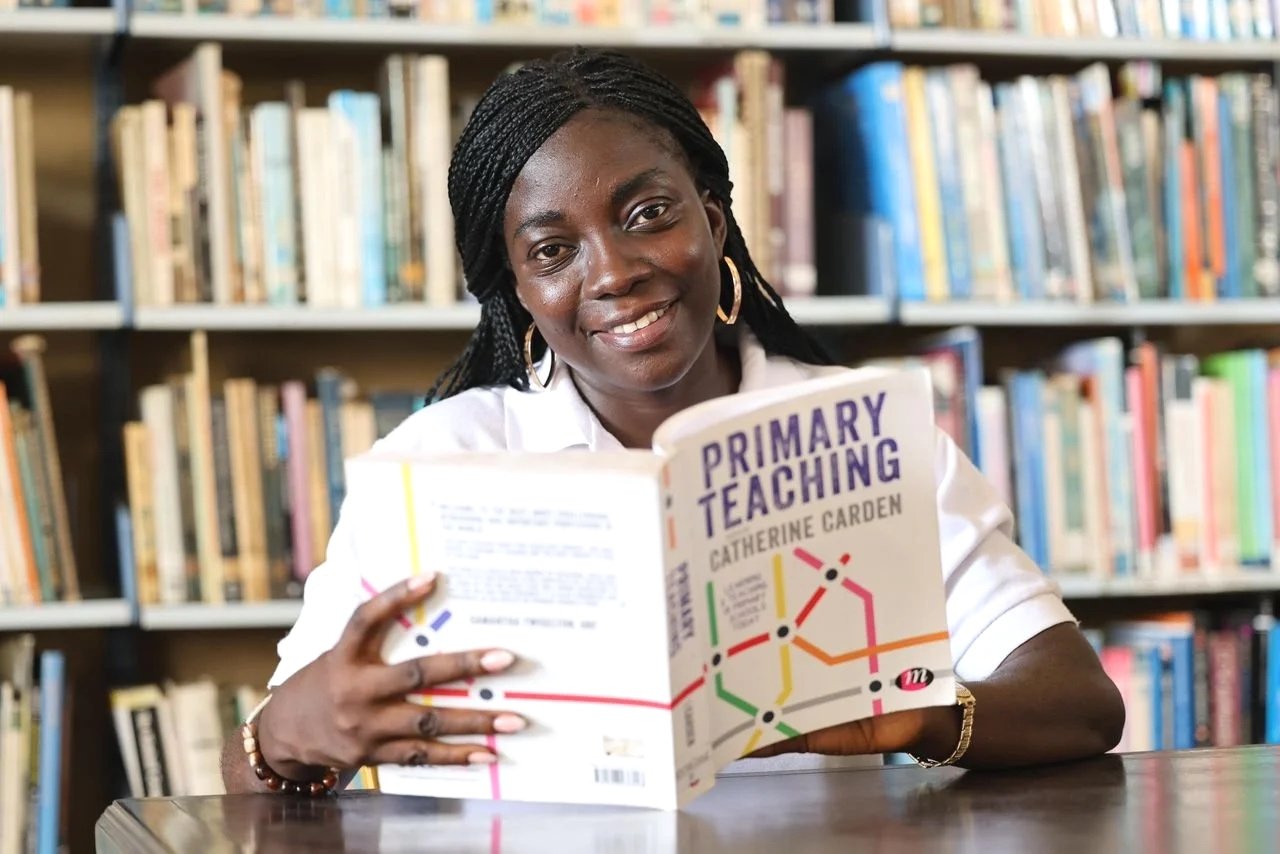

Dunstanette Bodkin, the Deputy Chief Librarian of the Sierra Leone Library Board.

Dunstanette I.O. Bodkin is the Deputy Chief Librarian of the Sierra Leone Library Board. Before attaining this position, she was the children’s librarian in the Children’s Department and an administrative assistant and programmes officer, respectively. She holds an M.Phil. in Library, Archive and Information Studies, a Bachelor of Arts with Hons in Library, Archive and Information Studies, and a Diploma in Library, Archive and Information Studies, all from Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone. She is a trainer and facilitator of literacy development-related workshops and programmes. She has attended and co-hosted literacy and early childhood conferences, seminars, and workshops in the country and outside Sierra Leone.

In 2023, she participated in the Library Aid Africa’s Young African Library Leaders Fellowship, a visionary program that prepares young librarians to become catalysts for change in the library ecosystem. Upon completion of the fellowship programme, she continuously participates and engages in early childhood literacy development activities and technology-related courses to promote her passion both as a passionate and a tech librarian. In this virtual interview with Poda-Poda Stories, Bodkin spoke to Ngozi Cole about the importance of childhood reading and why public libraries will always be relevant, even in the age of AI.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ngozi Cole: Dunstanette Bodkin, welcome to the Poda-Poda. Can you tell us a bit about yourself?

Dunstanette Bodkin: I've been working for the Sierra Leone Library Board for the past seven years. I studied Library Information Studies at Fourah Bay College. I started with a diploma program, then moved on to a BA Honors degree, and finally earned my Master's in the same field. I started as the children's librarian and then became an administrative assistant. But I continued working with the children's department because it is my special calling. No matter where I find myself, I always ensure that I work with kids, encouraging them to read and teaching them how to read as well. Recently, I was promoted to the Deputy Chief Librarian of the Sierra Leone Library Board.

NC: Congratulations! What made you want to become a librarian in the first place?

DB: It’s quite a story. I never really intended to become one. I loved books, and I loved reading, but there was nothing about librarianship because, growing up, you’re taught to aspire to become a lawyer, doctor, or engineer. But after my GCE O’levels, I looked out for different programs at Fourah Bay College where I could start a diploma course, and then I got to know about the Library Studies department, and I was like, okay, this sounds nice. The moment I started the diploma program, I just knew there was no turning back because I fell in love with it. After that, I enrolled in the BA program and graduated as a top student. But back then, no one saw the value of librarianship. I had to promote and advocate for Library Studies students to be valued and appreciated on campus.

NC: I'm a huge fan of librarians and libraries. My dad worked briefly at the Sierra Leone Library Board, and I got a library card really early on. Thank you so much for your work! As a librarian, how do you see people, especially children, using libraries? What are people using the libraries for, and how is that translating into literacy and reading in Sierra Leone?

DB: The Sierra Leone Library has 24 branches across the country, and our key patrons are children. We have a special department in our libraries called the children’s department or children’s corners. We have been able to partner with Book Aid International UK, and they have been very supportive of the children's corners and children's department. When you come into these libraries, you'll notice that the children's department is a special place, very well organized with books, toys, and games, designed for children. We always organize activities for them because having the children come in is one thing, but what would make them stay? It is activities across all our libraries, and we have several planned throughout the year. As long as you can get children reading when they’re young, it's best.

Getting adults to use the library is a bit trickier, but we do have them coming in, especially from colleges and universities, because we have those who understand the value. We have research materials and historical materials. Sometimes, people doing research struggle to find certain information, but when they come into the library, we have all these materials ready for them to use. That's the kind of service that we are providing for everyone.

Even though we are now competing with technology, we still know our place in society. We know that we are providers of relevant information. We know that we are curators of historical knowledge. In fact, we have a policy that all authors, both within and outside Sierra Leone, who write about Sierra Leone, should deposit three copies of their book with the Library Board for free. It's called a legal deposit, and all those who comply have their materials in the library.

NC: What are some of the challenges that the library is facing currently?

DB: A big challenge is finances. Sometimes we have late allocations coming in or allocations being cut off, so we have to manage resources all the time. An important thing about libraries is our programming; if we don't have the support we need, we lag and need to catch up with trends, but that’s difficult because of funding. For instance, for now, we really want to see how best we can go digital with our resources and how we can change our acquisitions department from traditional to digitized. But we can't do that. We still have to go through the hard labor of stamping them and punching cards, even though that's what makes us librarians. We also want to offer more programs for adults, like workshops on leadership and climate change, but we don’t have the funds.

Another challenge we are facing is transportation. We have 24 libraries across the country, and it’s hard to monitor them. We also need to take books to rural areas all around Sierra Leone. That’s why we are still trying our best to get our job done and stay relevant in the midst of all the challenges.

Dunstanette Bodkin also runs a non-profit organisation advocating for early literacy development and children’s welfare, Dunamis Kids Organisation.

NC: Can you talk a bit more about the organization you started, Dunamis Kids Organization, why you started it, and some of the initiatives you guys are working on?

DB: I used to have some family members sending me books because they just knew I was passionate about books and reading. So, they’ll look around to see what books they can collect and send to me, and I’ll make donations and distribute them to schools. So, with the knowledge from the Early Literacy course I took with the African Library and Information Associations and Institutions (AfLIA), I decided to team up with colleagues to see how we can put our limited resources, knowledge, and passion together to reach more children. Since we launched, we have been targeting schools and communities. So, for schools, we normally try to see how best we can help them set up the school library and support them in running it. And then, for the community, we normally organize pop-up libraries and reading activities with children. We’ve also been going as far as the children’s hospitals, where we launched a bibliotherapy initiative, emphasizing that even books can support healing. We’ve been to some hospitals, where we share stories with the children and also donate a certain number of books for the nurses to keep in the children’s wards, so the children can access and read them. We’ve also had community play-day activities where we merge play and reading, often during the Christmas break. In fact, we have a school where we set up both a computer room and a library, using computers donated to the organization from someone in the UK. We just blended that with some books we had, and we teamed up with the school authorities. They welcomed the idea, so now they have a library and computer room up and running, and that has helped to boost literacy in the school and engage the children in learning activities.

NC: Why are libraries so important, not just for kids, but adults as well?

DB: We tell people to see the library as a hub and a space that can provide many opportunities. People are not aware of how rich our collection is, and the whole idea of saying “Oh, I can just go to ChatGPT and get all that I want”, for example, isn’t really true. People have to understand that these things are not human. They make mistakes. There are so many errors, and for people to even use this tool successfully, they have to learn how to use it properly. As librarians, we have the capacity to know how to arrange information and how to determine relevant information for use. Not everything available online is true. You have to know how to verify and analyze your information. These are all things people aren't aware of; they just feel they don't need the library, but we keep telling them to come to the library. In fact, not everything in the library is online. We have some historical records in the library that you cannot find on any digital database. We know we are relevant, but then even within the field, we have colleagues who no longer want to be librarians. Now we have many colleagues with first degrees in librarianship, but they are rushing to pursue other fields because they don't feel comfortable in their own skin. But we try to have conversations where we can tell ourselves how much we matter.

There’s a lot of talk about Sustainable Development Goals or SDGs. You cannot leave libraries behind in that because there is a way the library can help to reach those goals, whether it is education, climate change, or entrepreneurship. We are a space where people can think together and offer solutions. The moment we gather for events and workshops, there's going to be a spark of ideas and solutions.

NC: Thank you, Ms. Bodkin. A final question: How have books saved your life?

DB: If I didn’t have access to books and stories growing up, I don't think I would've been able to get to where I am right now, because there is something about childhood reading that never leaves you. It helps you dream and imagine where you want to go and what you want in life. Sometimes people say, “Oh, you speak so well”. And I believe that didn't even happen in school or university. It's from my childhood, having access to good books and stories. I am where I am because of the books I read as a child.

Nationhood, Narrative, and Naming: Foday Mannah On Writing and His Debut Novel, ‘The Search for Othella Savage’

Foday Mannah is a British-Sierra Leonean writer and educator based in Scotland. Raised in Sierra Leone, he studied English Literature at Fourah Bay College and later earned advanced degrees in conflict and creative writing in the UK. His debut novel, The Search for Othella Savage, won the 2022 Mo Siewcharran Prize. His fiction has been recognized by the Bristol Prize, Commonwealth Short Story Prize, and others, and published in Wasafiri, Doek, and others.

The following interview took place via zoom between Mannah and Poda-Poda Stories’ associate editor, Charmaine Denison-George. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Charmaine: Welcome, Foday. I’ve been looking forward to this call with you.

Foday: Thanks for having me, Charmaine.

Charmaine: When did you first realize that writing was something you needed or wanted to do?

Foday: I think in high school. I went to Bo School in Sierra Leone. In form six, we had a current affairs club that also had a newspaper. We called ourselves the Satellite Newspaper. By then, because the country was going through a civil war, we focused on the activities of the war from the perspective of us students. So, my first entry into writing would be nonfiction, whereby I was the editor of the newspaper articles we wrote. I also had this strong tradition of reading quite a lot and later, when I became a teacher, I was exposed to a vast array of literature, so I ended up more or less reading and writing.

Charmaine: Every writer has a unique preoccupation with certain themes or tropes or arguments. What are these for you? Which ones have you explored in your already existing work and which ones do you hope to explore further?

Foday: I think it's power, definitely power. I’ve tried to examine the representation of power, both the domestic and political, especially in our societies. You would know this yourself, Charmaine, that as a child growing up in Sierra Leone, you hardly have a voice. Whatever the adults say is gospel. I’ve always been intrigued how that more or less translates to the political sphere. When I was a young man in Bo town, I remember that a government minister once arrived five minutes into a football match. I remember him walking in and the stadium with thousands of people went quiet. Then the Chief ran towards the referee saying, “stop the game, stop the game.” So, we restarted the game just because the minister had come. It was things like that that always got me thinking about how power operates.

Also, if you live in a society like Sierra Leone where almost everybody believes in Christianity or Islam, if you can harness that power and convince people that you are a proxy, that translates into astronomical power. And I think a lot of the times women are at the center of it, because women who don’t have a husband or children for example are seen as being defective, and sold remedies that they need to go to church and get prayers so they can get pregnant. So even though religion is at the center of my novel, and even though it's a crime novel, my obsession or my main focus is power, and how power can get manipulated both in domestic situations and political situations.

Charmaine: Who are the writers—African, diasporic, or otherwise that have informed your craft?

Foday: Oh, that's a difficult one. Charles Dickens had a big impact on me. I remember reading Great Expectations when I was in form four in Bo School. I say Charles Dickens also primarily because his novels focused on the industrial revolution with themes like poverty and deprivation and abuse of children.

From an African perspective, it has to be Chinua Achebe. He was massive with books like Chike and the River, Arrow of God, and No Longer at Ease. And moving on to modern times, I would say Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. I think she's phenomenal for her fiction and nonfiction (which I teach in my classes). I teach in a Scottish high school with predominantly white kids and it's interesting exposing them to her brilliant text titled, We Should All Be Feminists for example.

Charmaine: Do you write with a specific audience in mind or does it come to you as you write?

Foday: My default position has always been Africa. I was born in London and went to Sierra Leone when I was six. I went to school there and then university before returning to the U.K. So, I think with that in mind, a lot of my context, a lot of my background has to be more or less Sierra Leonean. Other pieces I write look at the immigrant experience, about us Africans in the diaspora and how that translates.

There’s an activity I do with my students called Fantastic Tales whereby I get them to pretend they're animals for example, and so write a creative piece from that perspective. I'll say you could even write this from the perspective of a dog. For an European or American dog, you write about going to the vet or being taken for a walk, but those things cannot apply for an African dog, because an average African dog doesn’t go to the vet and nobody takes it for a walk. They'd go over their own walk. So I think with writing about humans and even things or ideas like feminism, the context alters depending on where the person is.

Charmaine: You’re active in writing short fiction and recently, long-form with your novel—what’s the main challenge for you in switching between the two formats?

Foday: Well, I think short stories are fascinating, Charmaine, in the sense that most of them require quite a specific skill where you have to work within a word count. They also give you an opportunity to produce something that you could view holistically as an achievement. It's almost like a rapper’s mix tape which can serve as a precursor to their main album. I have that same perspective with writing in the sense that short stories give you a chance to dip your toe into the writing and put yourself out there. Short stories, I think, are a very good way to get validation.

And then the correlation between short stories and novels is that a lot of the times, my short stories are actually sections from my novel even though quite a few are stand-alone pieces. While editing a whole novel for example, you remove bits from it but you can't throw it away, so that becomes a short story of its own. So that's more or less what I tend to do.

Charmaine: Have you ever struggled with the idea of genre? I know some diasporic African writers are sometimes peeved by the classification that their texts receive, especially as a work of fiction can bleed into so many different things. Do you believe in classifying texts? And if so, what should the first order of classification be? Is it where the author is from or genre?

Foday: I think there's a kind of snobbery at times with these issues. I think that the books that win the big prizes tend to be termed literary fiction and I find that's really quite problematic in the sense that I don't think genres are mutually exclusive. Frederick Forsyth, for example, whose phenomenal spy novels I grew up reading, never got nominated for the Booker Prize. He wrote The Day of the Jackal, which is about a secret assassin who wants to assassinate the president of France because he has granted independence to Algeria. That's a rich, political topic which won't get recognition because it's labeled a ‘spy’ novel.

I think increasingly, I am quite happy that the lines of genre appear to be becoming a bit more blurred. Black Panther is another brilliant example, where on the surface, it is like a big Marvel movie, but when you look at it, it's deeply political. Wakanda, this secret African country with all this technology, is a brilliant metaphor about race and blackness. It was quite interesting to see it nominated for best movie at the Oscars because normally, a superhero movie might not get those accolades, but at least the academy realizing that genres are not mutually exclusive is good. And I'm a bit afraid of myself, the very fact that I've written something that's termed crime fiction because where we come from Charmaine, it's automatically seen with suspicion. And I get that a lot from my friends who say, okay, so you've written this and what does it mean? If I, for example, had written about the Sierra Leonean civil war or political corruption, they’d easily understand but crime, they don't know how to take that seriously.

Charmaine: What was the order in which your novel, Othella Savage, revealed itself to you? Did you first aim to write into the genre of crime fiction or did the characters reveal themselves to you first? How was the idea born?

Foday: An opportunity came for a short story competition, and they wanted crime fiction. That's when I thought about a horrible case in Scotland about a nurse in December 2008, who was abducted in the winter and locked in the boot of a car. I also remember watching a documentary over a decade ago about rinsers and it was about these young girls who would find older men who could lavish money on them. So more or less, the reasoning of the story was the rinsers documentary, the woman in the boot and the whole idea of religion which I merged.

Charmaine: I wanted to talk about the idea of names and naming in your work. I’d read the story you published in Afritondo where the protagonist’s name is Amadu Palaver and immediately, I knew he was going to be a problematic character and then, of course, there's Othella, Ronald Ranka and others in The Search for Othella Savage. What’s the effect of those names and specifically, how do you use it in your writing?

Foday: I think names can be hugely symbolic, and a kind of way to represent something. For example, Amadu Palaver is a real person. That’s actually what people called him behind his back because nobody dared to say it to his face. He was a very violent and aggressive man who was always fighting people.

With ‘Othella’, I just liked the female version of Othello. If you read Othello, it's more or less a black man in a white society. So, I quite liked that correlation that these women in the story are black women in a white society. With the other names like ‘Ranka’, you would know in Sierra Leone that the word suggests that he is not what he seems, and that he has a proclivity for corruption. There’s also ‘Elijah Foot Patrol’ who doesn't drive, also inspired by a similar name from the African community here… and of course there’s a jolly and happy fellow so his nickname is Santa.

Charmaine: What was publication day like?

Foday: You’re a writer yourself, Charmaine. You just have no idea how things are going to be received. Seeing a review in The Guardian was unbelievable because I was in the same article as Stephen King. People have also been ever so supportive, buying the book and even the students and teachers at school ask me to sign it, saying do you mind? And I thought, do I mind? Of course I’ll sign it!

And like I always say, with writing, a lot of the time you exist on the margins, but then something finally switches to the limelight, and it opens so many doors. It’s also an industry where you don’t see many people who look like us. Even recently in Edinburgh, Scotland, you get to a literary event with hundreds of people but maybe only one black person. It's a fascinating dynamic.

Charmaine: So, I read elsewhere that this novel was ten years in the making. What do you now know ten years on about the process of writing a book from start to completion? What has this new aspect of authorship taught you?

Foday: I think I’ve learnt that you have to persevere. I don’t think you should have this attitude that people owe you something. You cannot have a chip on your shoulder. I, for example, applied to the University of Glasgow to do a Creative Writing degree and I was rejected so I applied somewhere else, and I got accepted. During that course, they paired us with people and there was someone who, when we produced our first piece, the lecturer found a problem with it. The person ended up quitting because of the feedback. So, my advice will be that you need to try hard, and it has to be something you enjoy.

In terms of writing a book, it's a long, hard process. I finished the degree in 2014, I didn’t get shortlisted till 2019; didn't win the competition till 2022 and then I finally got published in 2025. These are massive gaps of time. So, it's not easy at all. You need to take your time and see where it takes you.

Charmaine: Now that The Search for Othella Savage is out in the world, what conversations do you hope it sparks?

Foday: Well, I don't think the themes are revolutionary but themes like the abuse of women or the insidious nature of religion would be good ones for discussion.

For religion, I have nothing against religion. I think in society, religion can become this soft, easy target to attack, but I also think that religion can be tied to so much good in the world like education. Some of the best schools, globally, are religiously founded. Like in Freetown, some of the best schools like St. Joseph’s Convent, The Annie Walsh Memorial School, The Sierra Leone Grammar School, these are all Catholic or Christian schools. So, I do not subscribe to the view that religion is more or less a dark thing. I however believe that human beings sometimes take the reverence we ascribe to religion to dark places.

For example, when my stepmother visited Scotland years ago, she refused to wear trousers or long johns even though she was cold. She said her pastor back home said women should not wear trousers. When we took her to church, and we asked her how she found the service, she said, well the service was okay but the only problem was that the woman Pastor was wearing a trouser suit. Similarly, my sister died at 21 of a serious strain of malaria because family members took her to church instead of a hospital till it was much too late. So, I think we need to challenge ourselves and we need to ask questions. We need to question our politicians, we need to question our religious leaders, we need to question our parents.

Charmaine: What do budding Sierra Leonean and African writers need to know about the craft of writing?

Foday: We should try not to be restricted by genre. I think a lot of our conversations are still mired in the past: Achebe and Ngugi and Beti. And there’s nothing wrong with that; these are phenomenal writers, but some of these books were written in the '60s and we need to move it forward. We also have to move away from this concept that it's all about age whereby older writers resist reading works by younger writers. I think that's ridiculous. I mean, I've got here Nightcrawling written by Leila Mottley which was long listed for the Booker Prize. I think she was like 20 when she wrote it, but good literature is good literature. It can come from anywhere, and we need to look beyond age. It cannot also be that we always write about big things like slavery and immigration and Windrush. There is nothing wrong with these things, but we can expand them into other spheres.

Our writers also need to look at other art forms like movies. The movie, Get Out, for example is a horror movie with a brilliant message about race in America. As, writers and creatives, we need to expand our sphere in terms of themes but also in terms of genre.

If you think about the competition I won, it was specifically for ethnic minority people because the thinking is that ethnic minorities do not write crime. The following year, the same competition was for children's books and then fantasy books. So, my advice would be more or less that we need to open it up. Let's write crime, let's write fantasy, let's write magical realism. And there are so many stories. And we as a people know so much about magic realism like, mami water, devils and the supernatural. We have this in a folklore, so why should we not tap into them?

Charmaine: Foday, thank you so much. It's my wish that you continue this path not only for personal fulfillment, but also to put Sierra Leone on the map with your writing.

Foday: Thank you, Charmaine. It's been a pleasure. That Poda-Poda is a magazine that is our own (Sierra Leonean) is absolutely fantastic. Thank you so much.

Purchase a copy of The Search for Othella Savage here: https://www.quercusbooks.co.uk/titles/foday-mannah/the-search-for-othella-savage/9781529437065/#

Yarri Kamara on the importance of African translators in literature

Yarri Kamara is a Sierra Leonean-Ugandan writer, translator and policy researcher who has lived and travelled extensively in the Sahel. She has been awarded several translation grants and was a finalist for the National Translation Award in the US for her translation of Monique Ilboudo’s So Distant From My Life. Her own essays and poems have appeared on numerous platforms including Africa is a Country, The Republic, Lolwe and Brittle Paper, and her work has been translated into French, German and Portuguese. She recently co-edited the anthology Sahara: A thousand paths into the future (Sternberg Press). In this interview, Kamara talks to Poda-Poda Stories about the importance of literary translation in Africa.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ngozi Cole: You’re a writer, essayist and researcher. How did you get into literary translation?

Yarri Kamara: I saw it as a necessity. I like playing around with languages, but I was happy for many years just doing technical translations.I lived in Burkina Faso for 17 years, so I was reading a lot of African literature written in French during that time. I'd come across great work and then I tried speaking to my family who don't read French about these books, but the books weren't available in English. That’s when I started paying attention to what gets translated and what doesn't get translated.

Now, a lot of the Francophone African literature has been translated by non-African translators, which in and of itself is not a problem, but sometimes you come across some translations that are a little bit lacking in context. So you wonder how much of the local context of the way French is spoken and whether it is West African or central African, whatever the region is, how much that particularity did the translator understand and how much attention did they put into conveying that into the English form. When I came across a Burkinabe novel, So Distant from My Life—which was my first literary translation project— I read it and I loved it. And I thought, well I have many years experience translating, given not literary translation, but here I am thinking about why is it that there's so few African texts translated by Africans? This is my opportunity to change that. And so I jumped in and gave it a shot.

Ngozi: What was the translation process of So Distant from My Life?

Kamara: I came across the book at its book launch. I picked up a copy and I read it almost in one sitting. It's quite a short book, but I like the rhythm and humor in it. So then I went to meet Monique Ilboudo and I told her I was interested in translating the book and would she be fine with that? And she said, sure, go ahead. I started looking for grants and came across the Penn/Heim grant program. I sent off an application and continued translating, even though I had no funding secured yet. And the translation process in and of itself was just a lot of fun and easy, because I knew exactly where her characters were coming from. Ilboudo bases her characters on the youth that grew up at a certain time in Burkina Faso. I could see her characters and in my head I could understand their expressions,what the thought processes were underneath what they were saying.

Ngozi: What would be some of these gaps that you think are still holding us back in terms of literary translation, and what’s your mapping of the literary translation landscape in Africa?

Kamara: There are a not lot of African translators between European languages, for example English and French or English and Portuguese. And I think part of that is a reflection of how foreign languages are not taught particularly well in our school systems, because to be a good translator, you absolutely have to be able to comprehend everything in the source language. On the other hand, thankfully you do see a lot of literary translators working between African and European languages. In South Africa, there's a lot of support for working and translating with the local languages like IsiZulu, Xhosa etc. I think it was just a few months ago that a celebrated translation of George Orwell's The Animal Farm came out in Shona. So I think it's fantastic to see these African writers and translators who master the languages that a lot of them grew up speaking and that they're now bringing works written in English and sometimes written in English by African authors. There's also now an impetus for promoting literature in the Swahili language, and some of that also goes towards translating texts into Swahili. I think Abdulrazak Gurnah winning the Nobel Prize for Literature has given a boost to that because now you have international bestsellers that can be translated into Swahili. So I think there’s a lot of positive development.

If we come back to West Africa, my overall observation is that there's still a lot more texts written in English by West African authors being translated into French, though often that's passing directly through France because we have such big name writers writing in English and most French publishing houses are interested in them. A lot of English to French translators emerge from Cameroon just because of that unique situation that Cameroonians have where a lot of people who grow up bilingual within the European languages in addition to indigenous Cameroonian languages they may speak.

Portuguese speakers are in Portugal, Brazil, and then the three or four countries in Africa. But I do know a lot of publishers based in Angola or Mozambique that are actively looking for things to translate into Portuguese for the Angolan or the Mozambican audiences because there's quite some differences between African Portuguese and Brazilian Portuguese.

Because so much of the world functions in English and through English, you can already access quite a variety of literature within Africa. There are so many Nigerian writers and so many South African writers. So maybe it takes us English speakers some time to realize that we're missing out on parts of the world when it comes to literature. Both the publishers and readers are not that actively looking for works being translated into English by African writers writing in other languages. Whereas I think certainly the Portuguese-speaking Africans, and also the French-speaking Africans are much more curious about accessing what is being written by Africans in English.

Ngozi: You’re right, English speakers do read in a bubble because so much is translated for us. I read Han Kang’s The Vegetarian and I really enjoyed it! And when she won the Nobel prize for literature, there was a debate on social media about the translation of The Vegetarian and that’s when I thought, oh, of course it was originally written in Korean! How do translators strive to stay true to the original version of the text?

Kamara: I think that's why translation is an art rather than a science. It’s great that you enjoyed Han Kang’s The Vegetarian–I know the translator who translated it into English—and it didn't occur to you initially to think this was not written in English. I think that's a sign of a good translation where it feels like it was written in the language you're reading it in. At the same time, you're also able to glean the unique cultural world of the original author. I think that's the balance that translators are always seeking.

Ngozi: What have been some of the formative books or forms of literature that have shaped you both as a writer and a translator?

Kamara: I went to an international school and there was no African literature on the curriculum at the time, but I think that has changed now. As a young teenager, I did attempt to read some of the immediate post-colonial African writers. But I think I read them at the wrong time in my life. I found them very stuffy and that didn't appeal to me. I came back to African literature as an adult and fell in love . I read two remarkable memoirs by African writers: Equiano’s Travels, also known by its original title “The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa the African” which chronicles the life of an enslaved Nigerian, who later buys his freedom, and his travels from Africa to the Americas and through Europe. And the other, more recent, “An African in Greenland” by Togolese writer Tété-Michel Kpomassie which recounts his long trip to Greenland in the 1960s. The observations that these two travellers coming from an-as-of-yet unglobalized Africa make of the foreign worlds they encounter are fascinating and a refreshing alternative to the prevailing Eurocentric narratives of those times. These books really opened my eyes to the importance of us Africans chronicling our times for future generations. A recent book that I come back to a lot is Ben Okri's A Way of Being Free, which are just beautiful reflections on the work of writers, or more broadly the work of artists in society, and how do we navigate the joys and also the heavy burdens of what storytellers are trying to do. In that book, Okri talks a lot about the responsibility that storytellers have and the kind of courage they need to have to do it well.

"Storytelling is resistance"-Hickmatu Leigh on the power of visual storytelling

Hickamatu Leigh is an artist photographer, storyteller, and young feminist activist from Sierra Leone. Known for her impactful photography and filmmaking focussed on the lives and experiences of Sierra Leonean girls and women, her award-winning work includes honours from the Women Deliver Arts and Film Festival 2023, and the SDG Vanguard Award in 2024 from the UN Foundation.

Her film, Gboroka, which explores Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), has been selected for the African Film Festival in New York. Ahead of the screening, Leigh shares the inspiration behind the film and why African women’s stories are important.

Poda-Poda Stories: Let’s start with your journey with photography as your language. How did you choose photography as a medium, and what has that journey been like?

Hickmatu Leigh: I don’t think I chose photography,photography chose me.

For a long time, I lived in silence. Growing up, I began to realize how much our environment shapes who we become. In my community, we were taught that the things that happened to us especially as girls were normal. That to be quiet was to be respectful. That to question tradition or religion meant you were rebellious, ungrateful, or even sinful. But deep down, I kept asking: what about us? What about how we feel? What about our voices?

I was angry. I wanted to stand out. I wanted more.

After graduating with a degree in public health, I struggled to find work. I was home, idle, reflecting a lot and that’s when it hit me. I had always loved taking pictures. It brought me peace. It made me feel seen, like I was actually good at something. Friends and family would tell me, “You’re really good at this,” and for once, I decided to believe them.

Photography became my language during a time I couldn’t speak. I was in a dark place, feeling invisible and not enough. But through the lens, I began to reclaim my worth. I started to see the power of visual storytelling especially in a country where so many stories about women like me go untold.

Over time, photography transformed from a safe space into my purpose. It took me into rooms with UNICEF, WHO, Purposeful, winning awards and having international exhibitions. More importantly, it led me to myself. Through photography, I have healed. And now, as a new mother, it feels even more sacred. It’s how I speak to my child, my ancestors, and the world. It is how I remain visible, rooted, and free.

Poda-Poda: What is your creative process like as an artist working in visual storytelling?

Leigh: My creative process is deeply spiritual. It often begins with a feeling sometimes from a story I’ve lived, or heard, or imagined. It could be sparked by a conversation, a sound, or even a single image. But once the spark comes, I sit with it. I reflect. I pray. I ask myself: What truth are we trying to honor here?

I write. I dream. I talk to the people whose stories I want to tell. I let their energy guide me.

For me, visual storytelling isn’t just about aesthetics. It is about emotion, legacy, and truth. I let intuition lead the way. Whether I’m documenting girls’ voices or exploring the sacredness of womanhood, I always aim to show the beauty in the struggle. My images are often black and white because I want people to focus on the emotion, the texture and the story.

My photography is a conversation that speaks without shouting, one that honors identity, culture, and resilience. Through veils, masks, and raw portraiture, I try to reveal what has been hidden. My work is my voice. It is my resistance and my offering.

Poda-Poda: That’s a good segue into the next question, which is about your film, Gboroka. I love that your work focuses primarily on Sierra Leonean women and this movie tackles a very sensitive and complex topic in Sierra Leone. How were you able to handle that sensitivity and drive the discussion forward about FGM in your film?

Leigh: Gboroka is deeply personal. It is my story—our story.

In Sierra Leone, topics like FGM are often surrounded by silence and shame. But I know firsthand how powerful visual storytelling can be, and I knew this was a story that needed to be told. Not with blame, but with honesty. Not to condemn our culture, but to show all of it the beauty, the pain, the complexity.

As a team through AWATS (African Women and Their Stories), we approached it with a lot of care. We didn’t want to sensationalize the topic, we wanted to humanize. We centered the voices of women and girls. We listened. We felt. We allowed their truths to guide the narrative. Gboroka is a conversation starter. It’s powerful, it’s triggering, but it’s necessary.

The goal was never just to make a film, it was to open space. Space to feel. Space to talk. Space to imagine a different future for our daughters.

We have screened Gboroka in a few places so far and had two international film selections. Every time, it stirred something deep. We’ve now launched our impact campaign and are actively taking the film to schools and communities to continue the conversation and inspire change. That’s the power of art it reaches where words can’t always go.

A still from the film Gboroka, which explores FGM.

Poda-Poda: What was the writing process like when you were working on the film, especially from the perspective of merging the visual with narrative?

Leigh: When I was writing Gboroka, there were moments I genuinely felt afraid. I remember sharing the idea with my mom and my aunt and their response was, “This na society secret, dem nor dey pull am na doe.” That moment hit me hard. It reminded me just how deep and sacred this silence is. But it also fueled the urgency. There was a strong will in me to tell this story from my own perspective from the stories the women before me whispered, the things I had seen, felt, carried. I wanted it to be raw. I wanted it to be honest.

We wrote Gboroka from the heart. We didn’t sit down to create a script that explains everything. We sat in silence. We sat with the question of what it means when a girl can’t speak her truth, when she screams inwardly and is told to call it tradition. We didn’t want to preach. We wanted people to feel.

Because I’m a photographer first, I approached every scene like a still image. I visualized pain, hope, and resistance in motionless frames. And that’s why Gboroka has no dialogue intentionally. We wanted viewers to interpret it on their own terms, to confront their emotions, their discomfort, their memories. Every frame was deliberate carrying weight, grief, silence, but also beauty.

We wanted to show the richness of our culture, the rhythm, the colors, the rituals but also the parts we’re not allowed to talk about. The wounds hidden behind smiles. So Gboroka isn’t just a film. It’s a question. A mirror. And I’m proud we dared to make it.

Poda-Poda: What are you hoping will be the outcome of Gboroka when people watch it?

Leigh: I hope Gboroka lingers.

I hope it opens doors for conversations we’ve been too afraid to have. I hope it helps girls feel seen. I hope it challenges parents to reflect, and community leaders to protect. I hope decision-makers move from silence to action.

But above all, I hope it births empathy. Real change happens when people feel something deeply. Data doesn’t always shift hearts, but stories do. If Gboroka helps even one person see things differently, it has done its job.

Poda-Poda: Choosing a creative career in Sierra Leone, as you may know, is not an easy path to forge, especially as a woman. What has helped you in your journey, and what advice would you give to budding filmmakers?

Leigh: It hasn’t been easy. Some days, it still feels like I’m fighting just to be heard. But what keeps me grounded is my why.

I remind myself constantly of my purpose for the girl I once was who needed to see someone like me doing this work. I lean on my sisterhood, my partner, and my faith. And now, as a mother, I carry a new kind of fire. Everything I create now is also a message to my child. A reminder that their mother tried to shift something.

To young filmmakers, especially women in Sierra Leone: your voice is enough. You don’t need permission to create. Start small. Start honest. Build your tribe. Protect your vision, and don’t be afraid to feel deeply.

Storytelling is resistance. It is love. It is a way of remembering and a way of dreaming. The world needs your voice, don't be afraid to use it.

Gboroka will be screening at the New York African Film Festival in May.